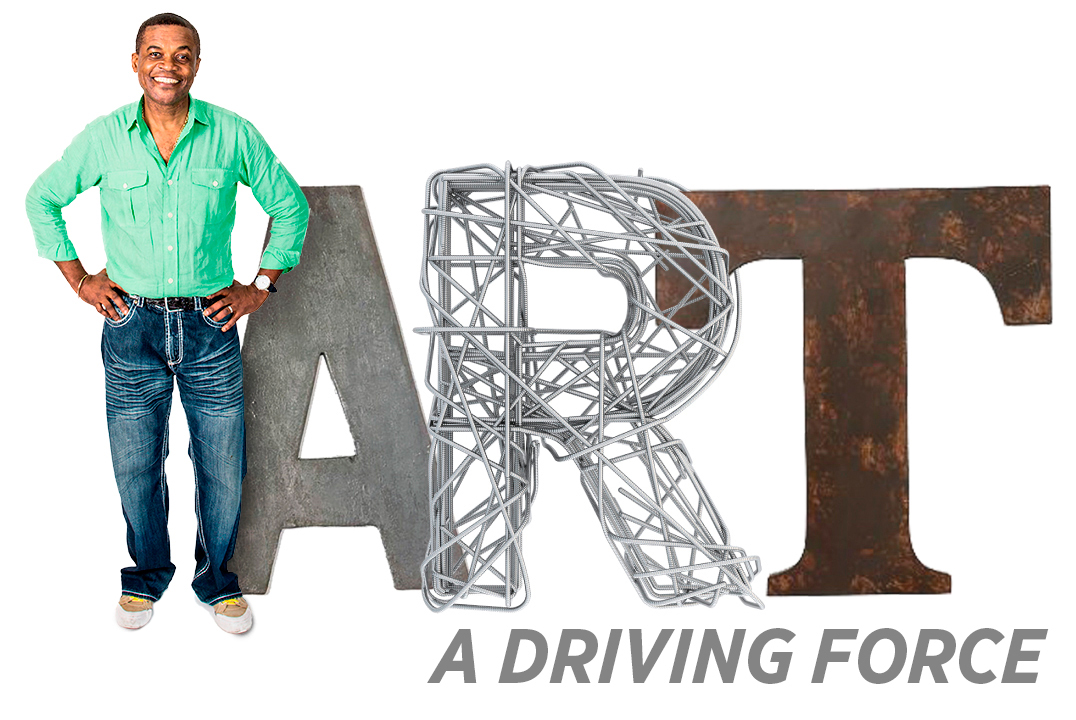

Art—A Driving Force

Sculptor Augie N’Kele was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa. In the 1980s, he immigrated to the U.S. to explore opportunities in art and education. He tells stories of Africa through his art.

"My country has a rich artistic and cultural history. The Congolese people have made important contributions to art and music," explained N’Kele. "One of my artistic goals is to introduce our history and culture to others. When you know Africa, you will love Africa."

After earning his Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting at the Academie Des Beaux-Arts in Kinshasa and Lubumbashi in 1979, he went on to study interior design at Notre Dame de la Sagesse in Brussels, Belgium.

N’Kele came to America speaking the Kikongo language as well as Lingala, Swahili, French and English. Upon arriving, he enrolled in ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) classes at Tarrant County College to further his English vocabulary and grammar.

He was a dedicated student and close with many professors, including Mary Williams, chair of the World Languages Department at the Northeast Campus.

"Augie was wonderful to have in class and to know outside of class," said Williams. "When a couple of colleagues and I were writing a textbook, we asked him to contribute his thoughts on the role of art in society. It was just what you would expect from Augie--intelligent, kind, rich in thought."

"He has a heart for humanity, a mind for history, a spirit that brings insight to all he does and an amazing talent for expressing all that through his art," she said.

During this time, N’Kele begrudgingly placed his art on the backburner as he struggled to earn money to move his family from Africa. Loneliness and homesickness soon set in. He worked humble jobs, sometimes 16 hours per day.

N’Kele's lowest point came when he received word that his mother had died from an automobile accident. One of his greatest supporters, his mother always encouraged N’Kele to follow his dreams.

Because he could not raise enough money to fly home for her funeral, he was denied the comfort and closure this "goodbye" would have provided.

For almost a decade after, N’Kele ignored his art. "From the loss of my mother, I lost inspiration. I could not create," he said.

During his years as a student in Africa and Belgium, he made side money sketching and selling portraits of the locals. A few sketches on scrap paper lay gathering dust in his closet. This was the only evidence left to remind N’Kele of his talent.

In the 1990s, he saw friends graduating from TCC and decided to enroll in a sculpture class.

N’Kele had not worked in a three-dimensional format before attending TCC, but quickly began to love creating art with his hands. During class, he experimented with plaster, wire, wax and clay.

"Augie was a star!" said Martha Gordon, associate professor of art at the Northeast Campus. "His personality and compelling story made him a joy to have as a student and a joy to call a friend. I still have one of his sculptures in my office as a reminder of Augie and his talent."

I have had many memorable students over the years, but Augie is perhaps most memorable.

Martha Gordon

Through sculpture, N’Kele found his voice as an artist. No longer satisfied with the sketches that were once his forte, he selected metals as his new medium. He used elements such as electric fence wire, aluminum mesh and found objects. He wove them into intricate works that portrayed African-American history and culture.

His sculpture work evoked the joy, pain, triumph and sacrifice of a time many would rather forget. His personal experiences compelled him to seek greater understanding of the past. He drew from childhood memories as well as events he had studied in Congo.

"It’s a story that needs to be told," he said. "You can’t build a future without knowing the past."

His first art show was at the Northeast Campus in 1991, when Arnold Leonard, former chairman of the Art Department, asked him to be a featured artist during Black History Month.

"This was my first public show, exposing my artwork to the community and the DFW media," N’Kele said. "It’s also where I met journalist Dorothy Hamm, who was a pivotal piece in exposing my art throughout the Metroplex and Texas."

"TCC opened the door to my future," he said. "I'm so blessed."

Another major turning point in his artistic career involved an unexpected meeting with Robert Glen, the Kenyan artist responsible for the Dallas landmark sculpture, Mustangs of Las Colinas. Glen asked N’Kele, who typically kept his work to himself, "What are you doing with your God-given talent, Augie? You are in a beautiful country and need to share your talent with America."

"Meeting Glen turned my life around and shifted my focus. Sometimes artists get lost and need to share stories and encourage one another," said N’Kele. "He helped me believe in myself and trust what I was capable of doing."

Soon after their encounter, N’Kele experienced an outpouring of creativity and began constructing his largest and most well-known series, Forgotten Heritage. The dozen pieces he first intended evolved into more than 200.

While in class at TCC, he prepared to add plaster to the framework of the first work in the series. N’Kele and his art professor, Karmien Bowman, took one look at the wire frame he had constructed and decided they liked it as it was.

"When he brought in the framework of scrap metal and wire, I told him not to plaster over it, that it was finished," said Bowman, associate professor of art at the Northeast Campus.

The raw framework became his signature look.

Once started, Forgotten Heritage took on a life of its own, becoming a central force in N’Kele's life. When he was not creating new works, he was conducting research.

N’Kele enjoys learning about different ethnic and national cultures. Having lived on three continents, N’Kele believes learning about other cultures allows people to understand and respect one another. Fueled by a deep desire to leave something of value for next generation, he looks for ways to unite people rather than divide them.

"Familiarizing yourself with other cultures is the most powerful tool one can use to bring people together in harmony," N’Kele said.

N’Kele has since had many successes as an American artist. A recommendation from the Dallas Museum of Art led to a PBS special, Art Journeys Gallery: Out of Africa into America, produced by the Art Museum of South Texas at Corpus Christi. The program, spotlighting N’Kele’s Forgotten Heritage series, was syndicated nationally in the late 1990s on PBS stations and broadcast to schools via Satellite in the Classroom.

Ithaca University in New York included N’Kele on a list of 20th century African-Americans who have made important contributions to the humanities for Forgotten Heritage.

N’Kele has exhibited throughout Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Iowa, Nevada, Oklahoma and the country of Norway.

His most current sculpture is on display at the East Texas Arboretum and Botanical Society in Athens, Texas.

He also conducts artist residencies, working with students from kindergarten through college in Irving, Dallas, Southlake and Fort Worth. His most recent residency was at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History.

N’Kele credits his family—wife, Anne Clarisse, son, Clarceet Augie and his newborn daughter, Anne Rachel—as his inspiration.

He also acknowledges the role TCC played in his success as an artist.

I will say this about my time at TCC… It was the best artistic decision I ever made in my life. I can’t talk about my art without talking about TCC.

Augie N’Kele

"I have shown my art at all TCC campuses, with the exception of Trinity River. But if you ask me to choose, I am biased to the Northeast Campus because that is where I attended and I believe it has the best art program out there."

N’Kele holds fond memories of walking the TCC halls. "This is my place. This is where I began."

An Interview with Augie N’Kele

Gallery of Forgotten Heritage Pieces

Click on an image below to view it in high resolution in a new browser window/tab.